Sudan’s conflict, far from being a regional anomaly, is spiraling further into disaster with no clear end in sight. The Sudanese Army, under the leadership of General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, has made significant military advances against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, aka Hemedti. Yet despite the army’s efforts, large swathes of Sudan remain in the hands of the RSF and various other armed factions, each controlling different parts of the country.

This war is about more than just these two forces. It’s a reflection of the decades-long instability that Sudan has endured, fueled by ethnic division, political corruption, and foreign interference. And despite the claims of victory from Khartoum, it’s evident that the war is far from over, with the RSF holding strong and numerous armed groups vying for control of Sudan’s territories.

The RSF’s Strongholds and the Military’s Struggles

In the urban centers like Khartoum, the Sudanese Army has been able to push back the RSF, but the situation is far from normal. The cities are left in tatters, their infrastructure shattered and civilians caught in the crossfire. But the real struggle is in the countryside. In regions like Darfur, the RSF remains a powerful force. They’re not just a paramilitary group—they are the legacy of the Janjaweed, notorious for their brutality during the Darfur conflict. The RSF controls large portions of the western and southern parts of Sudan, thriving on the chaos and instability that pervades these regions.

Despite some military victories, the army has not been able to completely dislodge the RSF from its strongholds. The RSF’s military capability is considerable, with the group having access to weapons, money, and support from several ethnic groups in Darfur and other marginalized regions. The RSF’s fighters know their terrain well, and their ability to mobilize quickly has allowed them to maintain control of strategic areas. In a conflict that is as much about local politics as it is about military might, the RSF remains entrenched in its areas of influence, and it’s clear the Sudanese Army will need more than just force to expel them.

Click to read about Abyei .

Other Armed Groups: A Fragmented Battlefield

Sudan is not a binary conflict between the Army and the RSF. The Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) includes several rebel factions from Darfur, the Nuba Mountains, and the Blue Nile, each with its own goals and motives. These groups, who have long resisted Khartoum’s central government, continue to hold sway in key parts of the country. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), for instance, operates in Sudan’s southern regions, pushing for autonomy and advocating for self-determination in the wake of the south’s secession in 2011.

On top of these, the Darfur-based Sudan Liberation Movement

(SLM) remains a significant player. Though their focus is primarily on securing justice and resources for the people of Darfur, they have also fought fiercely against the central government, contributing to the ongoing instability in the region. These armed groups are not just fighting for survival—they are fighting for relevance in a Sudan where control over land, resources, and political power is paramount.

Additionally, the conflict has spawned numerous smaller militias, each with their own interests. These tribal and regional militias have become increasingly powerful, often aligned with larger groups but maintaining their autonomy. They fight not just for political influence but for control over local resources, including gold, oil, and land.

Foreign Interests: The West, Russia, and China

While Sudan’s armed factions battle for control of the country, Sudan’s geopolitical landscape is equally complex. The West, with its endless calls for humanitarian aid, peacekeeping efforts, and diplomatic solutions, has done little to address the root causes of the conflict. The United States, the UK, and the European Union continue to pour resources into Sudan in the name of peace, but their involvement often exacerbates rather than alleviates the situation. Humanitarian aid, rather than being a solution, has

become part of what is often referred to as the “Peace Industrial Complex” in Sudan—an endless cycle of aid and intervention that fuels corruption, crime, and exploitation.

One glaring example of this is the presence of international aid organizations in Sudan, such as Israel Aid. The irony of these organizations offering “solutions” to Sudan’s crises, when their primary concern seems to be the acquisition of resources and international goodwill, is hard to ignore. Sudan, with its deep-rooted political and economic problems, has become a playground for these groups, many of whom have little genuine interest in resolving the conflict. The locals, who bear the brunt of the violence, often view

these foreign interventions with skepticism, questioning the real motives behind the humanitarian aid.

China and Russia, on the other hand, have largely steered clear of the moralizing that comes with Western interventions. They’ve maintained a more pragmatic approach, focusing on securing Sudan’s resources, particularly in oil and minerals. Their support for the Sudanese government is strategic, ensuring that Sudan remains in their sphere of influence. While the West criticizes

Sudan’s government, China and Russia keep their diplomatic and economic ties intact, carefully balancing their interests without the need for public posturing.

Click to read one of our previous pieces on Sudan

The Road to War: Why Sudan’s Future Is Bleak

Despite the military gains made by the Sudanese Army, it’s clear that the conflict is far from over. The country remains deeply divided, with powerful rebel groups controlling large areas of Sudan and continuing to challenge the government. The war is likely to continue, even if the RSF is defeated in

key urban centers. The Sudanese Army’s inability to fully control the regions still under RSF influence, combined with the growing presence of other armed factions, paints a grim picture for Sudan’s future.

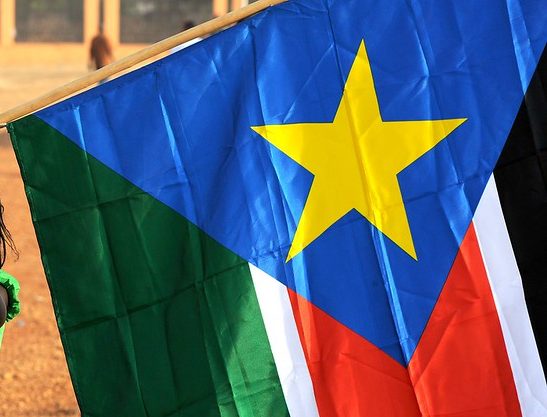

The international community, largely disinterested in Sudan’s long-term stability, has failed to offer any meaningful solutions. The West’s “humanitarian” efforts only seem to perpetuate the conflict, while China and Russia focus on resources rather than peace. In the end, Sudan will likely continue to fragment, with its people suffering in the aftermath. The world may offer platitudes, but much like the tragedy of Sudan’s neighbor, South Sudan, the world will soon forget.

For the Sudanese, the war is far from over, and the future looks bleak. With more armed groups fighting for control, a fragmented military landscape, and a world that has grown numb to the suffering, Sudan’s next chapter will likely be one of continued chaos—one that is unlikely to grab the attention of the West until it’s far too late.