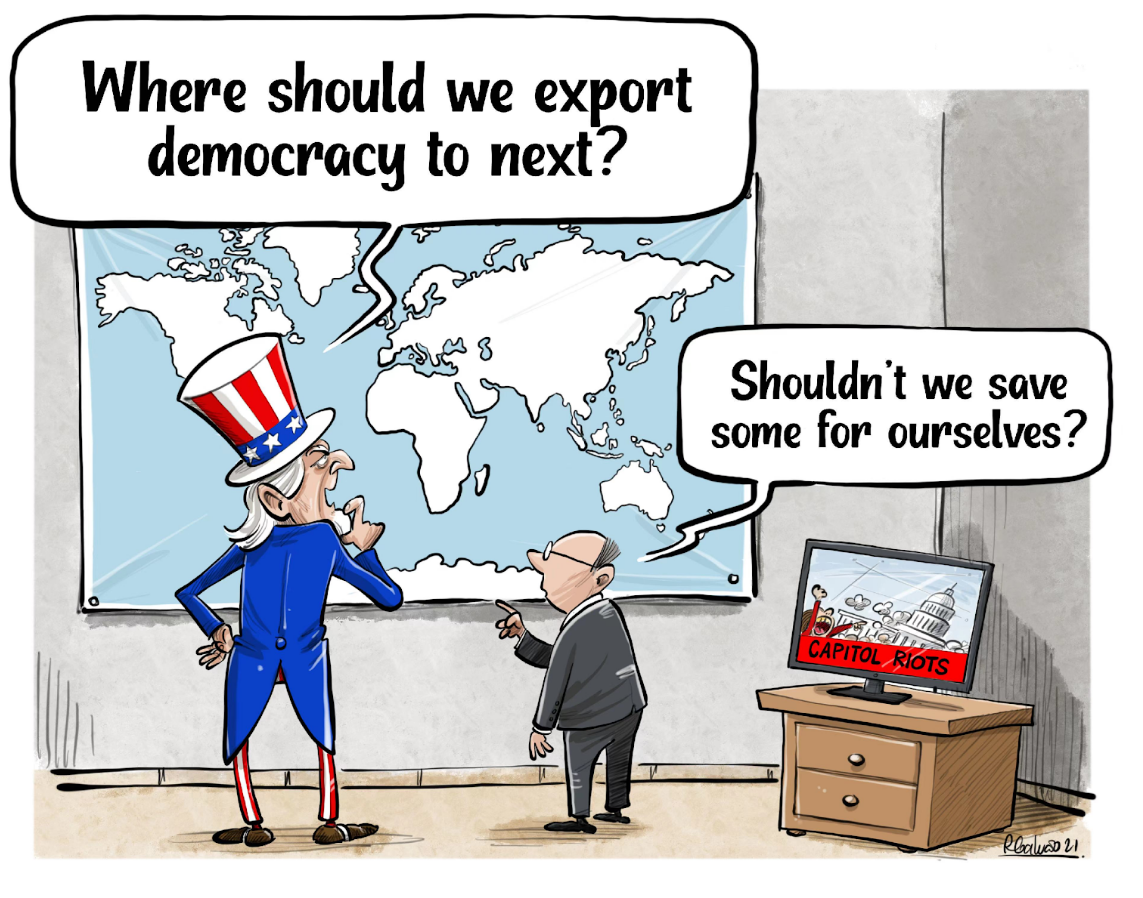

The U.S. has long spotlighted alleged election interference by countries like Russia, China, and Iran. Yet, as Ohio Senator JD Vance pointed out recently, the fixation on foreign meddling often overshadows America’s own extensive history of manipulating electoral outcomes worldwide.

This article unpacks how U.S. interference has not only influenced the trajectory of nations but also reveals a double standard: decrying meddling abroad while promoting its interests under the guise of democracy.

The Election Interference Double Standard

Allegations of foreign interference dominate U.S. discourse around election security, especially following the 2016 election. While there’s truth in claims that Russia, China, and others may dabble in influencing U.S. elections, the fact is that America has been doing this—and more—across the globe for decades. JD Vance, among others, calls out the hypocrisy in fixating on external meddling while overlooking America’s own interventions, which have arguably set more dangerous precedents.

The narrative holds that foreign influence threatens American democracy, yet U.S. leaders see fit to export their version of “democracy” abroad, often by means far more invasive than anything the nation accuses Russia or China of undertaking.

A Legacy of Overthrowing Democracies

One need only look back to the 20th century for proof of U.S. interference in democratic governments. Guatemala in 1954 saw a democratically elected leader, Jacobo Árbenz, ousted by the CIA after implementing agrarian reforms that threatened U.S. corporate interests. This left a trail of violence and instability that reshaped Central America for generations.

The U.S.- and UK-backed coup in Iran in 1953 removed Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, whose decision to nationalize Iranian oil challenged Western control over resources. This interference laid the foundation for the reign of the Shah, which ultimately led to the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the authoritarian regime in place today. If Iran had been allowed to follow its democratic path, the region might look very different. Such interventions highlight how U.S. influence on “democracy” often destabilizes and radicalizes regions rather than fostering real freedom.

More recent examples reveal similar patterns. Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan movement, hailed in the West as a pro-democracy uprising, has been seen by many as a Western-backed coup, which triggered Russia’s first invasion and laid the groundwork for today’s ongoing conflict. In a twist of irony, America’s push to counter Russia’s influence in Ukraine has resulted in one of the bloodiest conflicts Europe has seen since WWII.

Propping Up Yeltsin: America’s Hand in Russia’s 1990s Elections

The 1990s saw the U.S. make a direct impact on Russian politics, particularly in its support of Boris Yeltsin. In a country battered by economic turmoil, Yeltsin faced a possible defeat by the Communist Party. The U.S., under Bill Clinton, made it clear they wanted Yeltsin to win “so bad” that they intervened both publicly and behind the scenes to tip the scales. Clinton’s advisors even provided political support to Yeltsin, solidifying his position but at the cost of Russians’ economic stability.

While Americans saw it as a democratic victory, for many Russians, Yeltsin’s administration sold out the country’s assets to oligarchs, weakening Russia and contributing to the societal collapse. It’s no wonder that Yeltsin handpicked Putin as his successor, creating the adversary the U.S. faces today. The question remains: had Russia been allowed to shape its political path without external interference, would today’s geopolitical landscape look different?

[Related article: No Freedom of Speech in the Russian “Dictatorship”? Exclusive Eyewitness Report from a Protest Near the Kremlin in Moscow]

“Democracy” as a Veil for U.S. Interests

U.S. foreign policy promotes values often framed as democracy and freedom. But beneath this rhetoric lies a strategy of advancing American interests. Organizations such as the National Endowment for Democracy and groups like Radio Free Asia operate as soft power fronts, promoting narratives that align with U.S. goals. Nations compliant with U.S. interests are accepted despite questionable records, while those resisting Western economic or political norms are often punished.

Consider Taiwan, where U.S. rhetoric about protecting democracy escalates tensions with China. When Beijing attempts to secure its influence there, it’s denounced as interference, yet the U.S. persists in similar interventions across Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. America’s ability to frame its actions as virtuous while condemning similar tactics by others is a product of its control over the global narrative—a privilege nations like Russia and China rarely enjoy.

The Public’s Selective Appetite for “Honest” Leaders

In U.S. politics, there’s an expectation that leaders maintain the myth of moral superiority. But when leaders like Donald Trump call certain nations “shit holes” or candidly acknowledge “dealing with bad people,” the public reacts with outrage, less for the accuracy of the statement and more for the discomfort it provokes. America’s image is built on an illusion of moral high ground that voters demand but may not truly want.

Figures on the left, like Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, face backlash when they stray from mainstream foreign policy norms. Corbyn, for example, criticized Israel, breaking a longstanding taboo in U.K. politics and paying the price. Sanders, too, encountered resistance from a Democratic establishment reluctant to allow a shift toward a more isolationist or egalitarian stance. Even within its own system, the U.S. political machinery often marginalizes leaders who veer from established norms, casting doubts on the democratic credibility it champions globally. Ultimately, the outrage over foreign election meddling reflects a deeper discomfort with inconvenient truths. The U.S. public demands democracy, yet its leaders undermine it both at home and abroad. The obsession with foreign meddling in U.S. elections may be less about defending democracy and more about deflecting attention from the ways American influence has undermined democratic processes across the globe. While America champions the rhetoric of democracy, its actions often speak to a very different agenda and the fact maybe the US isn’t that great a democracy.