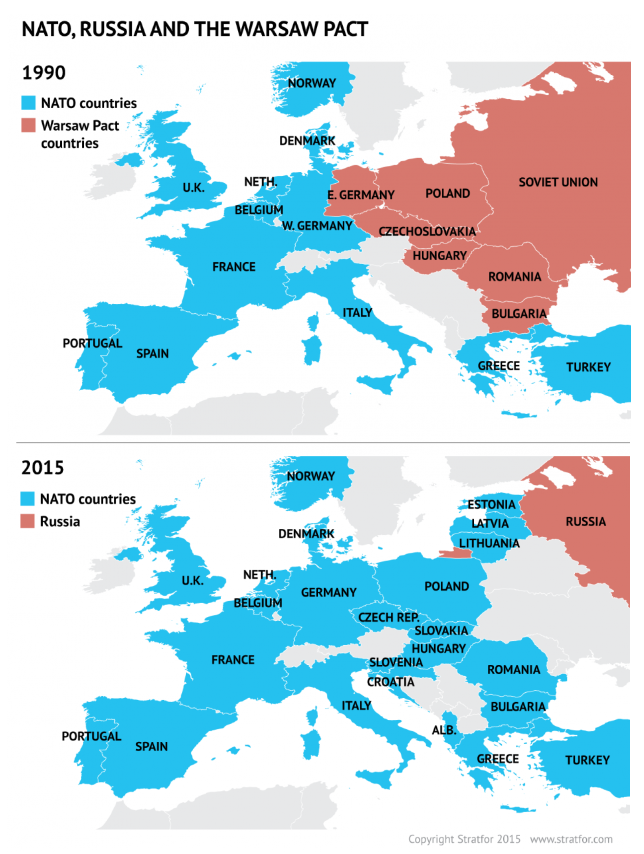

The Warsaw Pact dissolved together with the Soviet Union. With the elimination of the much-vaunted Warsaw Pact threat, NATO could also have dissolved. Instead it carried out its so-called eastward expansion, growing to 28 members, contrary to the commitment to expand “Not One Inch Eastward.” As a result, Russia felt increasingly encircled — and betrayed. (Graphic: Stratfor)

From NATO’s eastward expansion since 1999 to the 2015 Minsk Protocol and the March 2022 Ukrainian-Russian peace negotiations to the grain agreements of these days, Moscow has had bitter experiences with the West that leading political circles increasingly interpret as betrayals of Russia. In the following, we want to take a closer look at this view without having to endorse the military responses of the Russian side.

Perhaps it helps for understanding to start with a very big historical club, the German-Soviet non-aggression pact of August 23, 1939. In the West, this Hitler-Stalin pact, named after the most despised figures of the 20th century, is discussed mainly in relation to the fate of Poland. The division into German and Soviet spheres of influence in the Baltic States, which was also noted in the secret additional protocol, also continues to attract the attention of the historians’ guild. The breach of the treaty by Berlin on June 22, 1941, is imprinted on the collective Russian memory; in the German-language memory it goes by the name of the “invasion of the Soviet Union.”

The reference to the Hitler-Stalin Pact as an introduction serves to recall the historical moment of German, i.e. Western, betrayal in relation to the (Russian) East, apart from the moral classification of the power-political tussle between two dictatorships. Breach of treaty also seems to be a constant in the current relationship between the transatlantic alliance and the Russian Federation. And important broken promises emanate from Washington, Brussels and Berlin.

First, there is the eastward expansion of the transatlantic military alliance NATO. There is no written agreement that such an expansion would not take place after the withdrawal of the Red Army from the German Democratic Republic (GDR); the promise of a new, non-militarized world order, however, does. No less than the two chief diplomats of the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) faced the press a week before the decisive round of negotiations with Moscow on the withdrawal of Soviet soldiers on February 3, 1990. The German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher in the original tone: “We agreed (he meant himself and the US Secretary of State James Baker standing next to him, H.H.) that there is no intention to extend the NATO defense area to the East. By the way, this applies not only with regard to the GDR, which we do not want to incorporate there, but it applies quite generally.”[1] Genscher repeated this statement a week later in Moscow to his Soviet counterpart, Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze.

On March 12, 1999, less than two weeks before NATO’s first “out-of-area” deployment against Serbia, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland became members of the Western military alliance – and quickly found themselves in the war effort against Belgrade. In four further stages, by March 2020, eleven Eastern European countries (eight of them disintegrated products of the former multinational entities of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia) had joined NATO.[2] The military alliance’s further advance toward Ukraine was countered by Russia’s invasion on February 24, 2022.

In the summer of 2003, the Kremlin felt betrayed by Germany and France, which had just joined forces with Berlin and Paris to oppose the cruelly implemented omnipotence fantasies of George W. Bush’s U.S. government and had left him alone in his war against Iraq. Washington had been in an anti-terror frenzy since the events of 9/11 in 2001. For the armed campaign against Saddam Hussein, which had been justified with a brazen lie, the U.S. had to concoct a strange “coalition of the willing.” Its most important NATO allies, Germany and France, failed to cooperate.

In Moscow, this was interpreted as a turn from a bellicose transatlantic mood to geopolitical reason. The Kremlin was to be mistaken. In addition to the fact that German taxpayers were indirectly financing Bush’s war effort, it soon became clear that Germany’s foreign intelligence service, the BND, was actively involved in selecting targets for the bombing of Baghdad as a fire control center.[3] Russia remained alone in its opposition to the Iraq war. NATO ranks closed behind the Pentagon.

Perhaps the most important breach of trust in connection with the Ukraine crisis is the failure to implement the Minsk Agreement of February 12, 2015. In addition to a ceasefire, a prisoner exchange and a demilitarized zone, the agreement listed the federalization of Ukraine as a key political issue. The Minsk Agreement was intended to preserve the territoriality of the Ukrainian state (with the exception of Crimea) and to grant the secessionist regions in the east (Donetsk and Luhansk) extensive autonomy rights.

After the Ukrainian leadership soon made clear its unwillingness to implement it, the signatories Germany and France also failed to help the treaty, which is binding under international law as a result of UN Resolution 2202 (2015), achieve a breakthrough. For eight long years, the Minsk agreement lay in abeyance while the war in the Donbass waged by the Ukrainian army and right-wing volunteer units against the breakaway People’s Republics claimed thousands of lives. It was only after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, that the Western negotiators of Minsk then spoke plainly. François Hollande and Angela Merkel eloquently explained that Minsk had probably been concluded to buy time for Ukraine’s rearmament rather than to bring about a peaceful solution to the conflict. The Kremlin realized only very late how badly it had been bamboozled in Minsk and afterwards.

A further breach of trust on the part of the West occurred a few weeks after the Russian invasion, although it should be noted here that the invasion by the Russian army was not only illegal under international law, but also constituted a breach of the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, whereby Moscow had guaranteed the territorial integrity of the country in return for the Ukrainian renunciation of nuclear weapons.

As of March 10, 2022, just two and a half weeks after the attempt to overthrow the government of Volodymyr Zelenskiy failed, serious negotiations for peace began in Antalya, Turkey. Earlier, Russian-Ukrainian talks had also taken place in Gomel, Belarus, as well as intensive efforts to reach a cease-fire mediated by Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett. Turkey’s Antalya – patronized by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – saw high-level delegations from Russia and Ukraine led by Foreign Ministers Sergei Lavrov and Dmytro Kuleba.

By March 29, the so-called “Istanbul Communiqué,” as it had been formulated in the Dolmabahçe Palace, was available. This was a draft ceasefire agreed with Russian and Ukrainian negotiators that could subsequently have been signed at the highest presidential level. In it, Ukraine agreed to a declaration of neutrality and a renunciation of NATO membership and guaranteed not to allow foreign troops to be stationed on its territory. Russia, according to the communiqué, would have withdrawn its troops to the February 23 line, the day before the invasion. And, most hopefully, the status of Crimea would be decided within the next 15 years; in other words, the situation would have been defused to the maximum by the standards of the time.

As a gesture of goodwill, Moscow withdrew its troops from the area around the Ukrainian capital on this March 29, 2022. They had marched from Belarusian territory toward Kiev on February 24 to secure a planned elimination of the Ukrainian leadership by special units of the Russian army. At the time, Russian paratroopers wanted to advance into the center of the city via Kiev’s Hostomel factory airport in order to neutralize Zelenskiy and his military men. The venture failed due to the resistance of the Ukrainian armed forces. A 70-km Russian military column that had entered Ukrainian territory in the Chernobyl area was now stuck north of Kiev. Russian Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin justified their withdrawal on March 29, 2022, as a way to build trust for the draft cease-fire negotiated in Istanbul.[4] This, according to Russian delegation leader Vladimir Medinsky, also represents the first “steps toward de-escalation” of the situation.

Already three weeks earlier, on March 4, 2022, then Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett had launched a personal peace initiative. After a meeting with Putin, he spoke with Zelenskiy on the phone. “I was only the mediator,” he stated in a revealing interview[5] a year later. Bennett’s remarks give a clear indication that the West, especially the United States, did not want a cease-fire at that early stage.

“It may have been a legitimate decision by the West to continue fighting Putin,” says the Israeli head of state, showing understanding for his country’s biggest donor. To which the interviewer inquires, disturbed, “Fighting Putin? I think Putin is fighting Ukraine?” Bennett is not put off: “I’m talking about the aggressive (Western, H.H.) approach, and I can’t assess whether it’s wrong. But everything I did (in my shuttle diplomacy between Moscow and Kiev, H.H.) was coordinated down to the last detail, including with the U.S., France and Germany,” and could have resulted in a ceasefire. To which the interviewer responds, “So these blocked the initiative?” “Basically, yes,” Bennett answers spontaneously. “They blocked,” and adds thoughtfully, “I think that was wrong.”

Blockades against efforts for a ceasefire, of course, also existed in Russia and Ukraine. Ramzan Kadyrev, prime minister of Russia’s Caucasus republic of Chechnya, was just one of several prominent voices who strongly criticized ceasefire talks and, in particular, the withdrawal of Russian troops from northern Kiev. And on the Ukrainian side, even one of the negotiators of its own negotiating team had to jump ship. Denis Kireev, after returning from Gomel, where he discussed a possible silencing of arms with Russian representatives, was shot dead on March 5, 2022, in the open street by a task force of the Ukrainian domestic intelligence service SBU during his arrest. Kireev was working for the GUR military intelligence service.

Moscow’s military gesture to withdraw its troops stationed in northern Kiev on March 29 went unreciprocated. The Kremlin once again felt duped. Then, on April 1, the first reports of a massacre in the Ukrainian village of Butscha reached the public. Although the authorship has not been conclusively clarified to this day, this meant the end of all negotiations; on April 9, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson showed up in Kiev, having already warned President Zelenskiy in advance of his visit emphatically against making any concessions to Putin.[6] The prospect of a ceasefire receded into the distant future.

To make matters worse, Russia also felt betrayed in the grain agreement. The agreement, which was negotiated in July 2022 under the auspices of the Turkish president and the UN, was terminated by Moscow on July 17, 2023 after being extended three times. The reason given by the Kremlin was that even after one year, the negotiated mutual benefit for the Russian side was not given.

Although Russia, as one of the world’s largest exporters of grain, is also allowed to bring its cargo onto the world market, the financial and insurance service providers needed for this remain blocked by the U.S. and EU sanctions. The demand to at least reconnect the Russian agricultural bank Rosselchoss to the SWIFT system so that international money transfers can take place unhindered was not conceded by the Western side. Also, due to the sanctions, none of the major internationally active insurers are allowed to insure cargoes of Russian goods. So the (temporary?) end of the grain agreement is rooted, as so much is, in the lost contractual security and the many broken agreements that accompany the Ukraine conflict.

References:

[«1] Hans-Dietrich Genscher at the press conference in Washington on February 3, 1990, cf.: youtube.com/watch?v=o8rarwFKjw8 (27.7.2023)

[«2] In chronological order: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia (2004); Albania, Croats (2009); Montenegro (2017); Northern Macedonia (2020).

[«3] sueddeutsche.de/politik/deutschland-und-der-irak-krieg-jein-zum-krieg-1.893903 (27.7.2023)

[«4] sueddeutsche.de/politik/konflikte-krieg-gegen-die-ukraine-so-ist-die-lage-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-220329-99-709870 (28.7.2023)

[«5] infosperber.ch/politik/welt/nato-laender-haben-waffenstillstand-in-der-ukraine-vereitelt/; from minute 2:59:30 (27.7.2023)

[«6] dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/061/2006106.pdf; theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/28/liz-truss-ukraine-war-russia-conservative-power (27.7.2023)

▪ ▪ ▪

In this context Hannes Hofbauer has published “Feindbild Russland. Geschichte einer Dämonisierung” (Enemy Image Russia. History of a Demonization), Promedia Publishing House, Vienna