In the highlands of Laos, Hmong General Vang Pao recruited volunteers and conscripted soldiers from his tribe to fight in the CIA’s Secret War against the Pathet Lao and the Vietnamese allies on the Ho Chi Minh Trail through the country.. Revered by CIA Director William Colby as “the biggest hero of the Vietnam War,” Vang Pao’s legacy is fraught with complexity. Today, the Hmong people—descendants of the Mongols—maintain a quiet agrarian lifestyle, their once-thriving opium trade now banned. During my visit, their remoteness was palpable; I was the only tourist, a sign of their below-average prosperity.

Hmong village (Image Felix Abt)

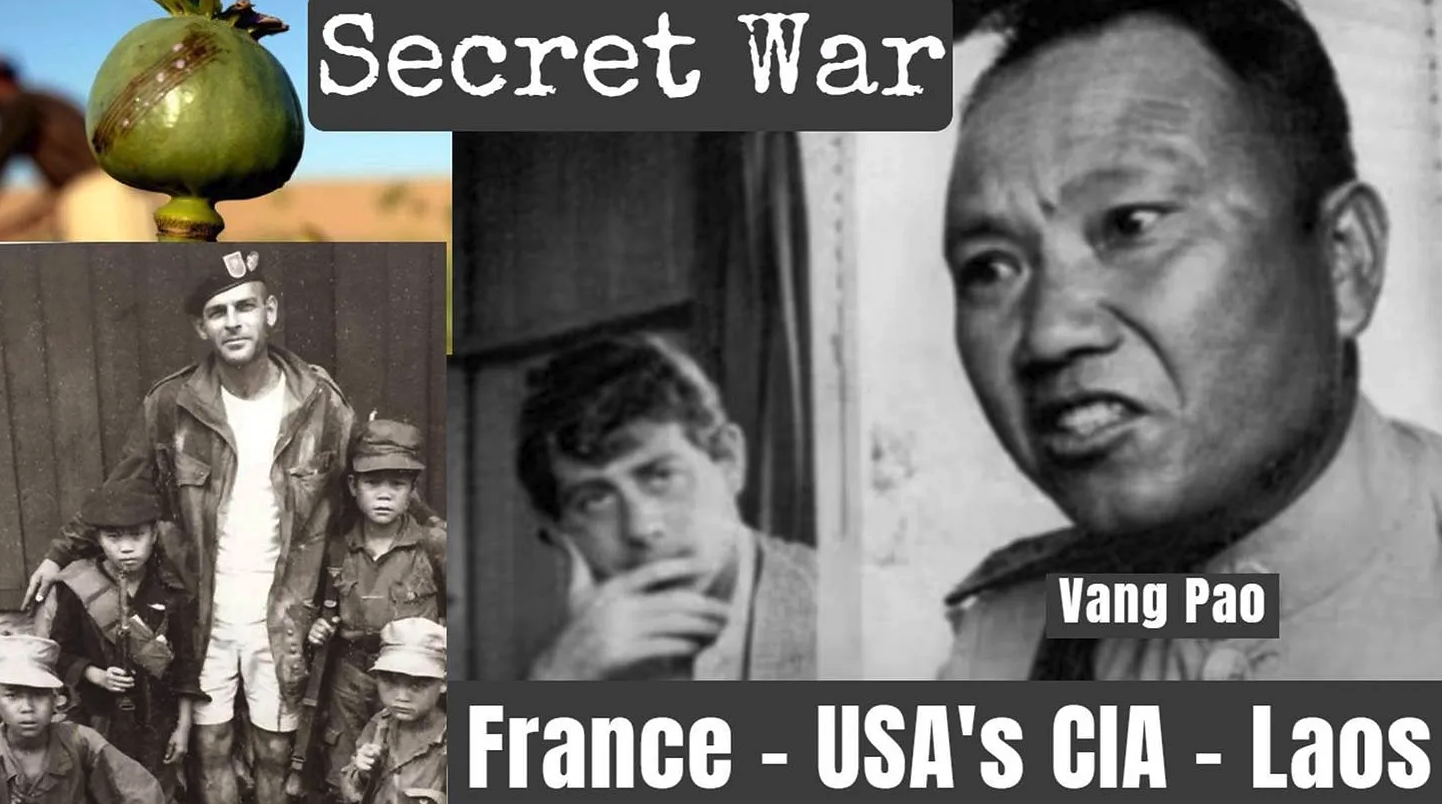

Opium, once central to the Hmong economy, became a geopolitical tool under French colonial rule (1940s–1950s). French intelligence leveraged the trade to fund anti-communist militias, exchanging arms for opium via initiatives like Operation X. After France’s withdrawal, the CIA inherited this system. By the 1960s, a small poppy plot could earn a Hmong family 100–100–200 annually—a fortune in Laos, where the average income was $70. The Hmong dominated opium production in Laos, and their crops were processed into heroin, which eventually reached the US troops in South Vietnam.

Tools the Hmong used to grow and harvest opium (Image Felix Abt)

Alfred McCoy’s seminal work, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972), details how CIA-operated Air America transported opium from Hmong villages to Long Tieng, the agency’s Laotian headquarters. CIA personnel, including pilot Neil Hansen and USAID officer Ron Rickenbach, witnessed opium loaded onto planes. Despite this, the agency denied involvement, citing national security. Vang Pao orchestrated the trade, purchasing opium above market rates to ensure loyalty. By 1966, his officers collected harvests from farmers, while rice shipments from the CIA freed land for poppy cultivation. Villages refusing conscription faced withheld rice and opium sales, forcing compliance.

The young man (left) told me that the Hmong were not united behind Vang Pao: There were Hmong like his own family who joined or supported the Pathet Lao.(Image Felix Abt)

The human cost was staggering. Vang Pao’s army, initially 40,000 strong, relied increasingly on child soldiers as casualties mounted. Edgar “Pop” Buell noted in 1968 that recruits included children as young as ten and men over 45, with a generation lost in between. By 1971, Hmong opium production plummeted to 30 metric tons from 100–150 tons. Meanwhile, heroin refined from their harvests inundated South Vietnam, addicting nearly a third of U.S. troops.

As the Pathet Lao advanced, the Hmong became refugees. Between 100,000 and 200,000 fled to Thai camps, while Vang Pao escaped via CIA helicopter to the U.S. By war’s end, 30,000–40,000 Hmong soldiers and countless civilians had perished—a death toll surpassing U.S. losses in Vietnam.

Laos, history’s most bombed nation, bears the scars of this betrayal. The Hmong, manipulated by French and American interests, were ensnared in a conflict that devastated their population and culture. Vang Pao, celebrated by some as a leader, remains a figure of violence and exploitation—a symbol of how Cold War machinations ravaged a people.

▪ ▪ ▪

A more detailed video version can be found here.