The Financial Times claimed that Chinese entrepreneurship had virtually disappeared as allegedly few new enterprises were founded last year.

I am writing this article to use current examples to show where the (manipulated) image that many readers have of China comes from.

I was recently in China and wanted to find out from Chinese people what the situation is regarding youth unemployment, which is portrayed as catastrophic in the West. I also had the opportunity to ask young Chinese people about the employment situation. You can find out more in my short video report here.

And no, I paid for my trip to China myself, received no compensation or reward from anyone and could film and photograph whatever I wanted without permission. Furthermore, I am not currently pursuing any business interests in either Russia (which I also visited recently and paid for myself) or China.

Here is a brand new example of how the economic situation in China is grotesquely distorted, not by the “New York Post” or “The Dail Mail”, which would be understandable, but by the prestigious “Financial Times”, which I have subscribed to as a businessman for as long as it has provided unbiased and reliable information. Even the once similarly reputable newspapers such as the “Handelsblatt” in Germany, “Les Échos” in France or the “NZZ” in Switzerland could never hold a candle to it. As a reminder, the NZZ, one of the most influential newspapers in the German speaking part of Europe, together with the German news magazine “Der Spiegel”, the “BBC” and the American mainstream media, also spread the fake news with great fanfare that Winnie the Pooh had been banned in China because he supposedly resembled President Xi Jinping and the latter was afraid of the cuddly bear. I have refuted this propaganda nonsense here with picture evidence. The Financial Times has set itself apart from them by not spreading this nonsense at the time.

However, the Financial Times’ China coverage has become increasingly one-sided, unfair and selective in recent years, following a general trend. As a reader, one had the feeling that journalists were obsessively looking for negative China stories to unsettle or frighten readers in the business world, rather than informing them objectively and fairly.

The Financial Times screwed up

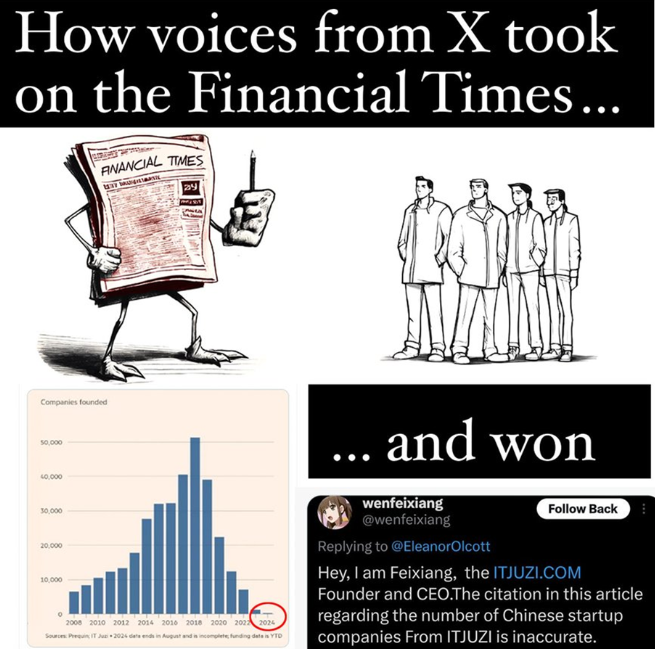

Last Thursday, the newspaper reported that Chinese entrepreneurship is almost extinct, as only 1,202 new companies were founded last year. Data from the Chinese monitoring service IT-Juzi was used as proof. The gloomy report and eye-catching graphic by FT journalist Eleanor Olcott (see below) was viewed over a million times on X (ex-Twitter). She seemed to have found the ultimate proof that Xi Jinping is about to completely eradicate the market economy in China.

Critical readers responded on “X” and pointed out that if you look at a single industry, e.g. restaurants, in a single location, e.g. a city, you can immediately see that there are a large number of new businesses. Multiply this by a country with a population of 1.4 billion and you get millions of new businesses — just like the official Chinese statistics say.

While the Financial Times (FT) claims that only ‘1,202 new startups were founded in China in 2023’, Chinese statistics show that 32.73 million new companies were founded in China in 2023. To be fair, not all of these 32 million companies can be considered ‘startups’ (however defined). The vast majority of these companies appear to be sole proprietorships, basically a type of limited liability company (LLC). Furthermore, many small businesses that are run as sole proprietorships do not necessarily go through a formal registration process and are therefore not statistically captured.

In the first half of 2024, 237,000 new AI companies were founded in China. At this rate, China is likely to establish half a million new companies in the field of artificial intelligence this year alone.

Aside from the data used by the FT for its false insinuation that ‘startups’ are funded exclusively by private VCs (venture capital firms), it should be added for completeness that the Chinese government is investing six times more to incentivise innovation in certain strategic sectors. This tried-and-true method has helped China’s industry become a global leader in electric vehicles, high-speed trains, alternative energy, telecommunications, and other sectors. Its industry leaders are mostly private businesses.

The debate on ‘X’ (ex-Twitter) took a new turn when investment specialist Glenn Luk (‘Glenn’) spoke up and pointed out the very mistake that the Financial Times had made. The FT had taken its figures from a narrow list, limited to start-ups financed by institutional investors and restricted to a specific time period. According to Luk, it is impossible to determine how many new companies have been founded in China on the basis of this data.

FT writer Eleanor Olcott defended herself with a post on X: “IT Juzi is China’s leading data provider on startups, tracking companies across basically every conceivable vertical that a VC would be investing in”. The London-based opinion editor of the Financial Times, Tony Tassell, praised the “great reporting” from his colleague “on how China has throttled its private sector and entrepreneurs”.

Finally, Wen Feixiang, the head of the company whose data was used by the Financial Times for its shocking graphic, also came forward on X: ‘Hey, I am Feixiang, ITJUZI Founder and CEO.The citation in this article regarding the number of Chinese startup companies from ITJUZI is inaccurate’.

He explained that his market research company’s list in no way reflects the total number of new companies in China. If even the source referred to by the Financial Times refutes the newspaper’s claim, wouldn’t the least they could do is retract the article and apologise to readers who have once again been taken for a ride with propaganda instead of information? So far, that has not happened.